I have a 1964 Chevelle with a small block and a TH350. It’s not a race car or anything—just a nice cruiser.

I’ve rebuilt the front suspension with new ball joints and control arm bushings and I’m getting ready to have the car aligned. I’ve also bought some new wheels and tires. I’ve been told that the stock alignment specs aren’t that great but I’m afraid I know nothing about alignments so I’m really in the dark with all the specs.

B.C.

You’re in luck because we can help you.

First of all, your friends are correct that the factory stock alignment specs are not very good for even mild street cruiser. Let’s run through what each spec is and how it affects the handling and then we’ll give you some decent specs that will apply to just about any 1960s-70s machine.

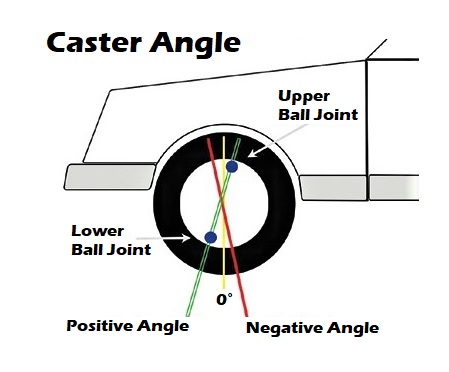

Caster

Let’s start with what is called caster. If we look at the left front tire from the side, imagine you can see through the wheel and tire and the orientation of the front spindle. If the spindle tips toward the front of car, this is negative caster. Conversely if the top of the spindle tips toward the rear of the car, this is positive caster. The more the spindle tips toward the rear, the more positive caster measured in degrees.

If you think of positive caster as like the angle between the spindle on a front bicycle wheel and the handle bars, you can see how positive caster creates forward stability—the front tires tend to want to remain pointed straight.

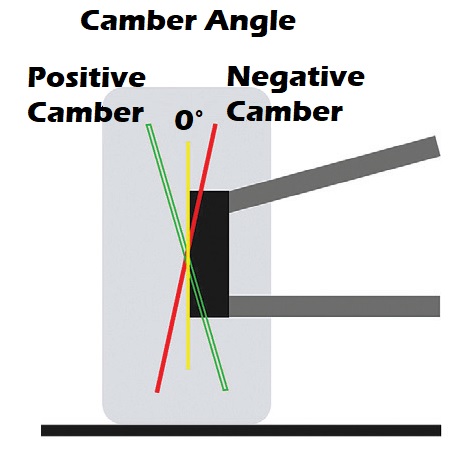

Camber

Our second alignment spec is camber. If you look at a front tire directly from the front, an inward tilt of the top of the tire (or spindle) is negative camber and an outboard tilt of the tire is positive camber. To improve handling, we want the front tire tilted slightly inboard with a slight amount of negative camber. This plants the outboard tire as you turn into the corner—like the right front tire on a hard left turn.

Sadly, most 1960s cars tend to suffer from an extremely poor camber curve that allows the tire to roll positive when the car is pushed into a corner and the suspension moves to compress the front spring. So in a hard left turn, the right front spring compresses and the camber curve allows the spindle to roll positive (outward) on the right front. That’s the exact opposite of what you want for better handling.

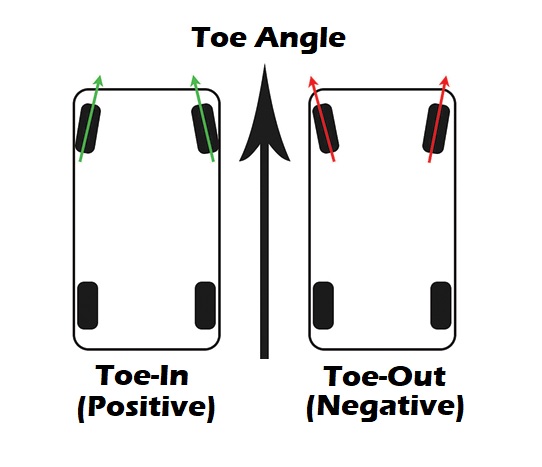

Toe

The last spec is toe. Looking at both front tires from directly from the front, toe-in is when the leading edges of the front tires point in. Toe out is the opposite with the leading edges of the tires pointing outward from straight ahead. A light amount of toe-in is usually good since forward vehicle motion tends to push the leading edges of the tires outward. This minimizes scrub as the car runs down the highway.

Ride Height

Before we begin to set the alignment, it’s important to emphasize that you will want to set the ride height with the springs and tires and wheels before taking the car to the alignment shop. This means both front and rear ride height. Any change to ride height will affect the alignment. So if you have installed new coil springs, you will want to drive the car for at least 75 to 100 miles to allow the springs to settle into their height before alignment. This is where coil-over shocks are nice since you can adjust ride height fairly easily.

Setting Proper Alignment

Now, we can begin to suggest some alignment specifications. As we mentioned, more positive caster will improve high speed stability so four to six degrees of positive caster is a good place to start. Essentially you want as much positive caster as you can get while still also establishing the proper camber.

For your street Chevelle, a good camber number would be about a 1/2-degree negative camber. With stock upper control arms and stock spindles, the camber curve is downright horrible because in a turn, the loaded side (right side in a left turn) will gain positive camber as the coil spring is compressed. This is the exact opposite of what you would desire. A much better situation would be to roll negative. Unfortunately, this situation is unavoidable with stock parts. A little negative camber will only slightly delay the roll to positive, but at least it helps. The final setting would be to set the toe-in at around 1/16-inch total between both front tires.

The best change you can make to improve handling would be with wider tires and a larger wheel diameter. In our Chevelle suspension exploits, we transitioned from 15 to 16 and then from 17 to now 18-inch diameter wheels with larger tires. As the sidewall gets thinner, the sidewall deflects less and more firmly plants the tread on the pavement. The down side to this is the ride quality suffers and you feel more of the cracks in the concrete.

If you want to further improve handling, a major step would be to increase the front sway bar from the small stock version to something around 1-1/8 inch. This will reduce body roll in the corners and also reduce the amount of positive camber gain. Good shocks would also be a major improvement. QA1 and Viking offer bolt-in quality versions.

The least expensive are the non-adjustable shocks. A good one here would be the Bilstein shocks for your Chevelle. A single adjustable shock most often will allow tuning the extension movement—pulled apart and often called rebound—but some single-adjustable shocks address the compression. A double adjustable shock will offer independent tuning for compression and rebound.

This is a little more input than what you originally asked for, but your Chevelle will respond to all of these upgrades and will handle far better than you might imagine. Have fun!

Comments